By Dan Steinbock

– Until recently, the US Fed ignored America’s soaring inflation. Due to its belated response, the consequent risks will penalize the ailing global recovery.

In November, U.S. inflation surged to near 40-year high, at 6.8%. Only days later, the Fed indicated it would end its pandemic-era bond purchases in March, thus paving the way for interest rate hikes by the end of 2022.

It had been one of the worst inflation calls in the Fed’s history. One that will contribute to new uncertainty in the United States. Nor will it spare the rest of the world, including the world’s most dynamic region – Asia.

The pandemic effects

For months, I, along with some observers, have been warning that what the US Federal Reserve have called “transitionary” inflation will prove not-so-transitionary and that it signals stagflation.

Through much of 2021, Jerome Powell, the chair of the Fed and his colleagues, characterized rising prices as transitionary. The rising prices would not leave “a permanent mark in the form of higher inflation.” But that was wishful thinking.

Since the early days of the pandemic, the Fed has made two mistakes. First, it began to cut rates belatedly only in March 2020. It ignored the WHO warnings and the drastic economic impact of the disruptive spread of Covid-19 in America. The mistake was amplified by the Trump administration that sought to protect US equity market, at the expense of American people.

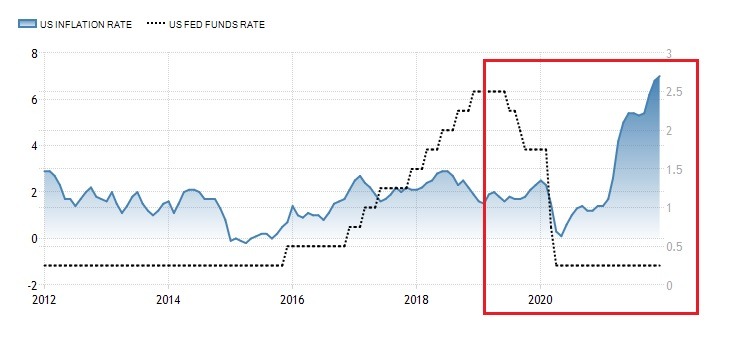

The second mistake ensued after mid-year 2021, when inflation began to climb rapidly. Instead of a timely response, the Fed signaled: This is not real inflation. It will go away. In reality, inflation soared (Figure 1).

Figure 1 10-year perspective: The Pandemic Effect

By November 30, Powell ditched the term ‘transitionary.’ But the Fed was months late.

Fed’s double-whammy surprise

The galloping inflation only worsened in December when inflation rose 7% from a year ago. Inflation was climbing at its fastest pace in almost four decades. Worse, it marked the fastest increase since June 1982, when inflation amounted to 7.1%.

President Biden’s approval rating had been falling ever since the rise of the inflation. Now widespread price increases fueled consumer concerns about the economy. As the net effect, Biden’s rating was tumbling.

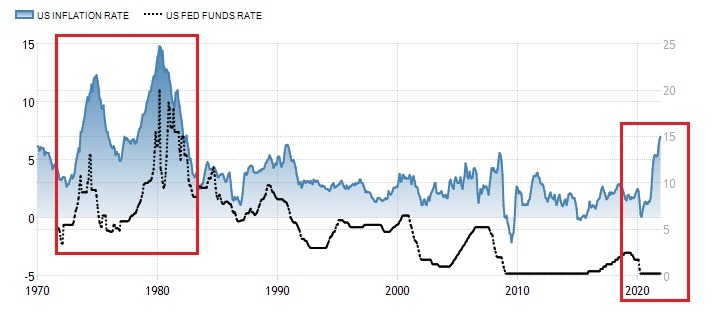

In the US, inflation rate and funds rate had moved fairly synchronously since the 1970s, when the Great Inflation had been stirred by two energy crises and price increases unmatched by productivity gains. As it morphed into persistent stagflation, then-Fed chief Paul Volcker resorted to record-high interest rates (20%+) causing a major recession in America, a lost decade in Latin America and extraordinary economic pain elsewhere.

Through fall 2021, the new stagflation – the combination of low interest rates and high inflation – has been untenable (Figure 2).

Figure 2 50-year perspective: Two Untenable Trajectories

The belated response will make things worse. The market had digested the Fed’s signaling it would hike short-term rates, starting perhaps as early as March. However, the bond market was hit on January 5, with the release of the minutes of the Fed’s Committee (FOMC) meeting in December 2021.

The unexpected surprise was that the Fed was also considering quantitative tightening; that is, shrinking its balance sheet. In addition to hiking the rates, it was planning quantitative tightening (as opposed to the past quantitative easing). That’s the double-whammy strategy that caught the market by surprise.

The challenges

Since the Fed awoke too late, it will have to hike rates faster and tighten already uncertain monetary conditions more than it did in the mid-2010s, in the aftermath of the 2008 crisis. And that will penalize the nascent recovery in America and contribute to still new delays in global recovery.

Second, a sustained rejuvenation of global economic prospects is predicated on growth, trade and investment. The Fed’s disruptive measures will weaken growth prospects, while the misguided US trade wars will further derail those prospects.

Furthermore, rate hikes and protectionism will add to global uncertainty, which will penalize foreign direct investment, while boosting “hot money”– speculative capital flows – that will add to market volatility.

Fourth, the combined effect could foster the return of the Republicans in the 2022 mid-term election and Trump’s comeback in 2024; neither of which is good news in view of the hoped-for global recovery.

Fifth, after the pandemic and the associated depression, U.S. sovereign debt is 131% of its GDP; not far from that of Italy amid the onset of the European debt crisis in 2010. The difference is that Italy, unlike the US, does not account for a fifth of the world economy, just as the old lira is not the major global reserve currency. US monetary policy has global repercussions.

Sixth, like Trump, the Biden administration calculated that debt-taking is fine since rates will remain low and interest payments manageable. They calculated wrong. As a result, Washington will continue to take more debt to (presumably) fight debt.

Finally, due to the impending rate hikes and quantitative tightening, the Fed impact will be felt throughout Asia where central banks are likely to signal more hawkish stances in the coming weeks.

While China may prove more resistant to the Fed impact, most of Asia won’t. While analysts expect China, Indonesia and South Korea bonds to outperform, Thailand and Malaysia bonds are likely to prove less successful. Recently, the Philippine peso plunged beyond 51 per dollar for the first time since April 2020 as the country’s trade deficit is expect to widen.

The Fed impact will cause further weakening in Southeast Asia in 2022.

Two black swans

There are two to black swans in play as well. The first may cushion the Fed impact worldwide; the second would magnify it.

Until recently, the optimists – foolishly – though that the Delta variant would be the last breadth of the global pandemic. Omicron proved them wrong. It will contribute to unanticipated challenges in the labor markets and new supply disruptions worldwide – and thus further sustain inflation.

Furthermore, due to the pandemic mismanagement and huge infection surges in the West, the pandemic effects may linger for months, perhaps even longer, thanks to inadequate global cooperation, politicized responses and vaccine inequality,

The other black swan is the Fed itself. The current stagflation has been fueled by the Fed’s policies and the Trump-Biden trade war.

With ultra-low rates and rounds of QE, the Fed took a risky path. That’s the message of Thomas Hoenig, former member of the Fed’s top policy committee (FOMC). This path, Hoenig says in the just-released The Lords of Easy Money will deepen America’s income inequality, stoke dangerous asset bubbles and enrich the biggest banks over everyone else. And if the Fed fails to exit its own money-printing quagmire, it could destabilize the financial system.

Unsurprisingly perhaps, when economic policies are misguided, threats of war and rearmament drives – from Ukraine to South China Sea – conveniently deflect and distract from the real economic challenges.

About the Author:

Dr. Dan Steinbock is an internationally recognized strategist of the multipolar world and the founder of Difference Group. He has served at India, China and America Institute (US), Shanghai Institutes for International Studies (China) and the EU Center (Singapore). For more, see https://www.differencegroup.net/