By Karen Jackson, University of Westminster and Oleksandr Shepotylo, Aston University

The ability to strike new trade deals was a key promise of the Brexit campaign, even before the UK left the EU. But progress towards a deal with the US has been stuttering. There were originally high hopes that an agreement could be ready for when the Brexit transition period ended on December 31 2020. So what’s the delay and what can the UK realistically expect to get in any such deal?

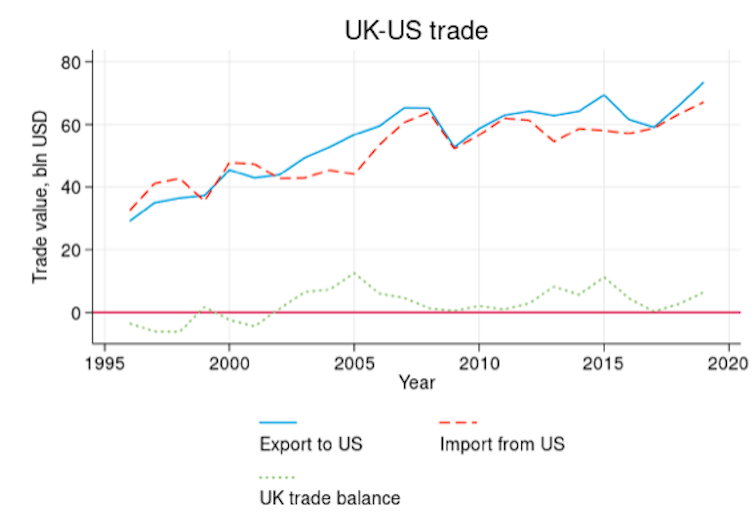

Trade between the UK and US reached an all time high of more than US$140 billion in 2019, according to UN COMTRADE and has been growing steadily for the past two years. Meanwhile, there was a slow decline in UK-EU trade in 2019 – although its value is still much higher at US$560 billion.

Provided by author, Author provided

But, as expected, UK exports and imports fell sharply in May and June 2020, with some recovery in July and August. It is clear that the 2019 growth in UK-US trade has been reversed, largely as a result of the pandemic. This makes UK-US negotiations on further trade liberalisation increasingly important.

Talks on a deal formally started in May 2020, and after several missed deadlines no arrangement has materialised so far. President-elect Joe Biden’s recent interview with the New York Times suggests there is little likelihood of the US striking a full trade deal with the UK in the short term. And when the US Trade Promotion Authority runs out in July 2021, there will no longer be an opportunity to fast track a deal through Congress.

However, recent comments from Robert Lighthizer, the current US trade representative, to the BBC have raised hopes of a mini deal, which might focus solely on bringing down tariffs.

Slow start

There are a number of reasons for the lack of progress: the US election got in the way, and the UK has been negotiating with a range of partners all at the same time. While the UK has one of the largest teams of trade negotiators, they are still new to this process, since all these arrangements were in the hands of EU trade negotiators until very recently. There are also substantial differences of opinion.

On healthcare, access to the UK market would be a good outcome for US negotiators, as representatives of the US healthcare sector are interested in expanding into the UK. However, UK negotiators have stated: “The NHS will not be on the table. The price the NHS pays for drugs will not be on the table. The services the NHS provides will not be on the table. The NHS is not, and never will be, for sale to the private sector, whether overseas or domestic.”

This being said, a U-turn is possible particularly if there is no other way to strike a deal. The NHS is so important in regards to a deal with the US that it may have to be re-examined.

UK exporters already have strong access to the US market; the US is the most important export nation for UK goods exports. On the other hand, there are more opportunities for better access to the UK market for US products. US negotiators are particularly keen for the agricultural and food sectors to be opened up. That said, the British public are becoming more informed of the potential issues with US food products being sold at lower than EU standards. And, understandably, UK farmers do not welcome increased competition.

From a UK perspective, there just doesn’t seem to be that much to gain from a trade deal in economic terms; the UK government’s own modelling estimates increases of 0.07-0.16% of GDP in the long run depending on whether the deal would lead to partial or full trade liberalisation. For the US, a deal would only start to look more economically beneficial if the UK is willing to open up the food or healthcare markets, both of which are politically very difficult. However, a deal would be highly symbolic for the UK as it tries to find its place in a post-Brexit world.

While it is unlikely we will see a full UK-US trade deal in the near future, it is possible that we will see a mini-deal emerge during the final weeks of the Trump administration. This might see the two countries agreeing lower tariffs on products such as whisky and cashmere. Alternatively, under the next US administration, Biden’s keenness to build alliances against China could also encourage a UK-US mini-deal.![]()

About the Author:

Karen Jackson, Senior Lecturer in Economics, University of Westminster and Oleksandr Shepotylo, Lecturer in Economics, Aston University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.