By John Hawkins, University of Canberra

A year ago, El Salvador became the first country to make Bitcoin legal tender – alongside the US dollar, which the Central American country adopted in 2001 to replace its own currency, the colón.

President Nayib Bukele, a cryptocurrency enthusiast, promoted the initiative as one that would deliver multiple economic benefits.

Making Bitcoin legal tender, he said, would attract foreign investment, generate jobs and help “push humanity at least a tiny bit into the right direction”.

His ambitions extended to building an entire “Bitcoin city” – a tax-free haven funded by issuing US$1 billion in government bonds. The plan was to spend half the bond revenue on the city, and the other half on buying Bitcoin, with assumed profits then being used to repay the bondholders.

Now, a year on, there’s more than enough evidence to conclude Bukele – who has also called himself “the world’s coolest dictator” in response to criticisms of his creeping authoritarianism – had no idea what he was doing.

Free Reports:

Get our Weekly Commitment of Traders Reports - See where the biggest traders (Hedge Funds and Commercial Hedgers) are positioned in the futures markets on a weekly basis.

Get our Weekly Commitment of Traders Reports - See where the biggest traders (Hedge Funds and Commercial Hedgers) are positioned in the futures markets on a weekly basis.

Sign Up for Our Stock Market Newsletter – Get updated on News, Charts & Rankings of Public Companies when you join our Stocks Newsletter

Sign Up for Our Stock Market Newsletter – Get updated on News, Charts & Rankings of Public Companies when you join our Stocks Newsletter

This bold financial experiment has proven to be an almost complete failure.

Making Bitcoin legal tender

Making Bitcoin legal tender meant much more than allowing Bitcoin to be used for transactions. That was already possible, as it is in most (but far from all) countries.

If a Salvadoran wanted to pay for something in bitcoins, and the recipient was willing to accept them, they could.

But Bukele wanted more. Making bitcoins legal tender meant a payee had to accept them. As the 2021 legislation stated, “every economic agent must accept Bitcoin as payment when offered to him by whoever acquires a good or service”.

To encourage Bitcoin uptake, the government created an app called “Chivo Wallet” (“chivo” is slang for “cool”) to trade bitcoins for dollars without transaction fees. It also came preloaded with US$30 as a bonus (the median weekly income is about US$360).

Yet despite the law and these incentives, Bitcoin has not been embraced.

Greeted with little enthusiasm

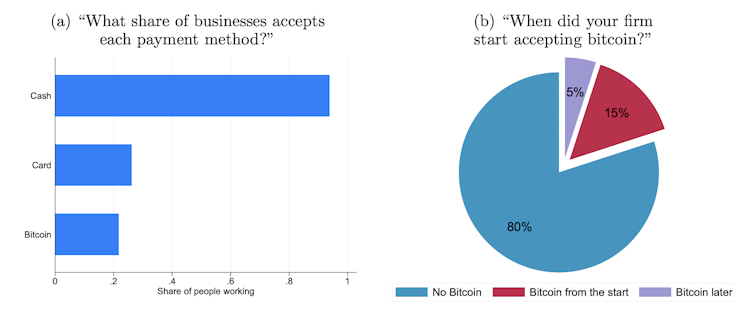

A nationally representative survey of 1,800 Salvadoran households in February indicated just 20% of the population was using Chivo Wallet for Bitcoin transactions. More than double that number downloaded the app, but only to claim the US$30.

Among respondents who identified as business owners, just 20% said they were accepting bitcoins as payment. These were typically large companies (among the top 10% of companies by size).

Business acceptance of Bitcoin in El Salvador

A survey for the El Salvador Chamber of Commerce in March found only 14% of businesses were transacting using Bitcoin.

Making huge losses

Fortunately for Salvadorans, nothing has come of the US$1 billion Bitcoin bonds scheme. But the Bukele government has still spent more than US$100 million buying bitcoins – which are now worth less than US$50 million.

When Bukele announced his plans in July 2021, Bitcoin’s value was about US$35,000. By the time the legislation came into effect, on September 7 2021, it was about US$45,000. Two months later, it peaked at US$64,400.

Now it is trading at around US$20,000.

Bukele has made self-congratulatory tweets about “buying the dip” but almost all the bitcoins bought by the government have been for more than US$30,000, at an average price of more than US$40,000.

A year ago, Bukele was urging his citizens to hold their money in bitcoins. For anyone who did, the losses would be devastating.

Flawed analyses

Bukele’s misunderstanding of Bitcoin – and economics more generally – has been demonstrated repeatedly.

In June 2021 he tweeted: “Bitcoin has a market cap of US$680 billion. If 1% of it is invested in El Salvador, that would increase our GDP by 25%.”

This suggests he seemed to think Bitcoin was some sort of investment fund. It also showed he did not understand GDP. Foreign investment is not a component of GDP. There has been no surge in foreign investment nor GDP.

In a January 2022 tweet he argued a “gigantic price increase is just a matter of time” because there will only ever be 21 million bitcoins while there are 50 million millionaires in the world. “Imagine when each one of them decides they should own at least ONE #Bitcoin,” he proclaimed. Bitcoin’s value has since halved.

The rest of the world is not impressed

The Bitcoin plan has adversely affected El Salvador’s credit rating and relations with the International Monetary Fund. With investors more wary of lending to the country, local borrowers have had to offer higher interest rates.

In January the IMF urged El Salvador to reverse Bitcoin’s legal lender status because of the “large risks for financial and market integrity, financial stability and consumer protection”. Bitcoin is notorious for its use in scams and other illegal activities, as well as its volatility.

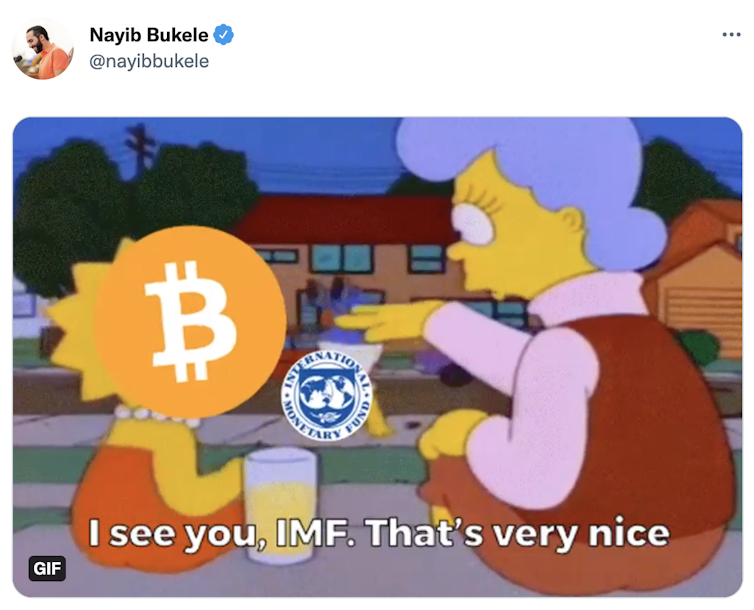

Bukele tweeted a dismissive response involving a Simpsons-themed meme.

Twitter, CC BY

This seems particularly rash, given El Salvador has been seeking a loan of more than $1 billion from the IMF.

International credit rating agencies Fitch has downgraded El Salvador’s credit rating this year, citing concerns about its Bitcoin policies.

No other country with its own currency, not even ones such as Zimbabwe and Venezuela with discredited currencies, has followed suit and made Bitcoin legal tender.

Given El Salvador’s record, it is is unikely any ever will.![]()

About the Author:

John Hawkins, Senior Lecturer, Canberra School of Politics, Economics and Society, University of Canberra

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

- Investors run to safe-haven assets amid Middle East escalation Mar 6, 2026

- EUR/USD Under Pressure: Middle East Risks Outweigh All Else Mar 6, 2026

- Bitcoin shows resilience to Middle East events. Oil market stabilizes Mar 5, 2026

- GBP/USD: Market Not Expecting BoE Rate Cut in March Mar 5, 2026

- Brent headed for $100? Mar 4, 2026

- Global stock indices continue sell-off due to Middle East conflict Mar 4, 2026

- USD/JPY to Quickly Return to Growth: Momentum Favours the US Dollar Mar 4, 2026

- European equities plunge amid Persian Gulf military conflict Mar 3, 2026

- Gold Rallies for Fifth Day, With External Risks Mounting Mar 3, 2026

- Iran Crisis: A Dangerous Turning Point Mar 2, 2026