By Karl Schmedders, International Institute for Management Development (IMD) and Patrick Reinmoeller, International Institute for Management Development (IMD)

Stock markets reached all-time highs in 2021, bringing huge value to the companies riding the wave, even when you allow for the dip in recent weeks. We are also in the midst of a boom year for flotations, with many boards taking advantage of investor enthusiasm for shares. Yet companies have been delisting from the stock market in even larger numbers, and, in fact, this trend has been going on for some time.

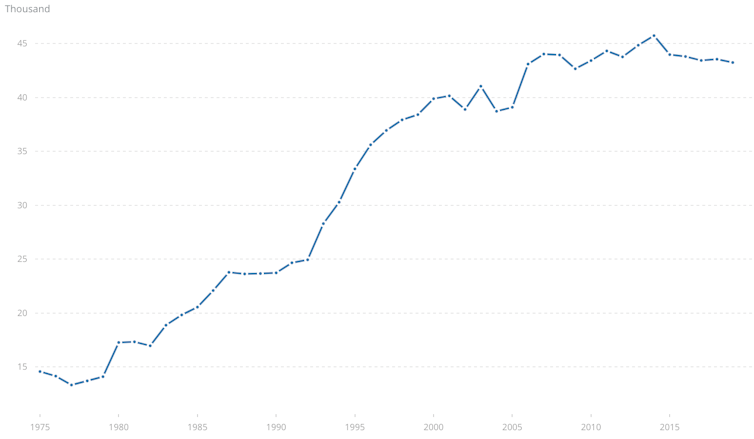

The number of listed companies worldwide peaked at 45,743 in 2014 but had slipped to 43,248 by 2019 according to the World Bank. The numbers in major markets such as the US, UK, France and Germany have all been trending down.

In 2020, there were 47 deals to take companies private worth a total of US$40 billion (£29 billion), which was well down from the 62 deals worth US$88 billion in 2019, though the numbers were considerably up in Asia. On the other hand, 2021 has been a huge year: going private is already beyond its previous peak from 2007, with a record number of transactions that has already surpassed US$800 billion.

Total listed companies worldwide

Some of these decisions to go private are being driven by aggressive buying by private equity groups such as Blackstone, KKR and Apollo. In the belief that there are corporate bargains in the wake of the pandemic and Brexit, these investment firms did US$113.5 billion worth of deals in the first half of 2021 alone. That’s more than double the previous six months and the strongest half year since the first half of 2007.

Free Reports:

Get our Weekly Commitment of Traders Reports - See where the biggest traders (Hedge Funds and Commercial Hedgers) are positioned in the futures markets on a weekly basis.

Get our Weekly Commitment of Traders Reports - See where the biggest traders (Hedge Funds and Commercial Hedgers) are positioned in the futures markets on a weekly basis.

Sign Up for Our Stock Market Newsletter – Get updated on News, Charts & Rankings of Public Companies when you join our Stocks Newsletter

Sign Up for Our Stock Market Newsletter – Get updated on News, Charts & Rankings of Public Companies when you join our Stocks Newsletter

Yet the lure of private equity is not the only explanation for companies walking away from the stock market. So what’s going on, and are they doing the right thing?

The big turn-off

For one thing, there is enough money to be found elsewhere that companies don’t need to raise funds through a flotation. The world’s central banks have been increasing the money supply by slashing interest rates and “printing money” via quantitative easing (QE) since the financial crisis of 2007-09, but the latest round of QE in response to the pandemic has taken this to a whole new level. The current rate of money-supply expansion is faster than the growth of economies. With lending rates so low, all this money is chasing investments. A stock-market listing begins to seem tedious when you can just borrow money very cheaply instead.

The second attraction with being private is regulation. Listed companies have become tightly regulated on the back of corporate-governance disasters such as WorldCom, Enron, Galleon Group and more recently Wirecard. These constraints have motivated many a company to skip public scrutiny by choosing to be private instead.

Another problem with public markets is how illogical they have become. Now that amateur traders can buy and sell shares easily through platforms like eToro and Robinhood, company valuations are at the mercy of their whims. Witness GameStop and other shares going through the roof earlier this year thanks to the Reddit group WallStreetBets.

Amateur traders can also choose to automatically copy the trades of professionals or celebrity traders on a platform like eToro. One celebrity trader’s decisions in the market can mean that many people make the same trade, increasing volatility across hitherto unrelated assets.

Equally, tweets and memes can send valuations soaring or sinking. A good example was Elon Musk driving up the price of dogecoin by making positive noises about the cryptocurrency on Twitter, including referring to himself as the #Dogefather. No wonder many company boards would rather keep away from such a volatile environment.

Is it worth it?

Sometimes when business leaders have decided to go private in the past, they have reversed this later. For example, Michael Dell took his computer company private in 2013 only to re-list it five years later. He had got the business into a stronger position that he felt would be recognised by the markets. Musk himself has mused about taking Tesla private, having felt that the car company was being undervalued by the markets in the past, though now it’s a different story after the share price has surged in the past couple of years.

Neither is an improvement in a company’s market sentiment the only argument for staying listed. The greater transparency can be a selling point to investors, and selling shares to them is not the only way to take advantage of this. Companies can always opt for loans or bonds as alternatives – and hence limit their exposure to social media influencers and amateur traders.

And instead of living in fear of negative sentiment, companies might see it as a challenge and reflect on how to better respond. This might involve intensifying their public relations, advertising and lobbying strategies to better explain the company to the outside world.

Company executives can still be hurt by big shifts in their share price because this is typically one of the performance indicators that determines what they get paid. But again, delisting isn’t the only way around this problem. Instead, companies can rethink their performance indicators – perhaps putting more emphasis on environmental performance, for example, in anticipation of the fact that regulations in this area are bound to increase.

One other potential medium-term advantage to being listed relates to regulation. The more companies that go private, the more likely that regulators will impose more rules on them to protect their investors and prevent fraud. They might even be tempted to increase taxes on private companies to make up for the lack of regulatory scrutiny. In this sense, the allure of going private might turn out to be fool’s gold.![]()

About the Author:

Karl Schmedders, Professor of Finance, International Institute for Management Development (IMD) and Patrick Reinmoeller, Professor of Strategy and Innovation, International Institute for Management Development (IMD)

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

- COT Metals Charts: Speculator Bets led by Silver, Gold & Platinum Mar 7, 2026

- COT Bonds Charts: Speculator Bets led by 10-Year Bonds & Fed Funds Mar 7, 2026

- COT Energy Charts: Speculator Bets led by Brent Oil & Heating Oil Mar 7, 2026

- COT Soft Commodities Charts: Speculator Bets led by Corn & Soybean Meal Mar 7, 2026

- Investors run to safe-haven assets amid Middle East escalation Mar 6, 2026

- EUR/USD Under Pressure: Middle East Risks Outweigh All Else Mar 6, 2026

- Bitcoin shows resilience to Middle East events. Oil market stabilizes Mar 5, 2026

- GBP/USD: Market Not Expecting BoE Rate Cut in March Mar 5, 2026

- Brent headed for $100? Mar 4, 2026

- Global stock indices continue sell-off due to Middle East conflict Mar 4, 2026