By Dan Steinbock

– Thanks to the containment failures of Covid-19 and the resultant new variants, coupled with vaccine inequality, global prospects are overshadowed by economic apartheid – the polarization between the West and poorer countries.

Today, sub-Saharan Africa is in the grip of a third wave, parts of Latin America continue to see high levels of new deaths, and concerns remain about the Covid-19 situation in parts of South and Southeast Asia.

In Africa, the highly infectious Delta variant of coronavirus is spreading like a wildfire. Infection numbers have soared for 1.5 months with 224,000 new cases being recorded every week. Due to the low degree of testing, detection and vaccination, real numbers are much higher than official estimates.

In the past decade, the economic prospects of Africa have been touted as the “next big thing.” While development is unbalanced across the region, many countries have great secular growth potential. But Delta and other variants could derail that promise.

We are witnessing a disruptive shift from vaccine inequality to economic apartheid.

Free Reports:

Download Our Metatrader 4 Indicators – Put Our Free MetaTrader 4 Custom Indicators on your charts when you join our Weekly Newsletter

Download Our Metatrader 4 Indicators – Put Our Free MetaTrader 4 Custom Indicators on your charts when you join our Weekly Newsletter

Get our Weekly Commitment of Traders Reports - See where the biggest traders (Hedge Funds and Commercial Hedgers) are positioned in the futures markets on a weekly basis.

Get our Weekly Commitment of Traders Reports - See where the biggest traders (Hedge Funds and Commercial Hedgers) are positioned in the futures markets on a weekly basis.

From Asia to UK and Delta variant

In early February, when the official narrative was that “the worst is over,” there were more than 110 million (confirmed, cumulative) Covid-19 cases and over 2.5 million deaths. Today, barely half a year later, the number of cases has almost doubled exceeding 200 million, while deaths have soared to 4.3 million. In both cases, real numbers could be two to three, in some cases even four times higher.

How did the international community end up in this dire status quo? The simple answer: In three phases.

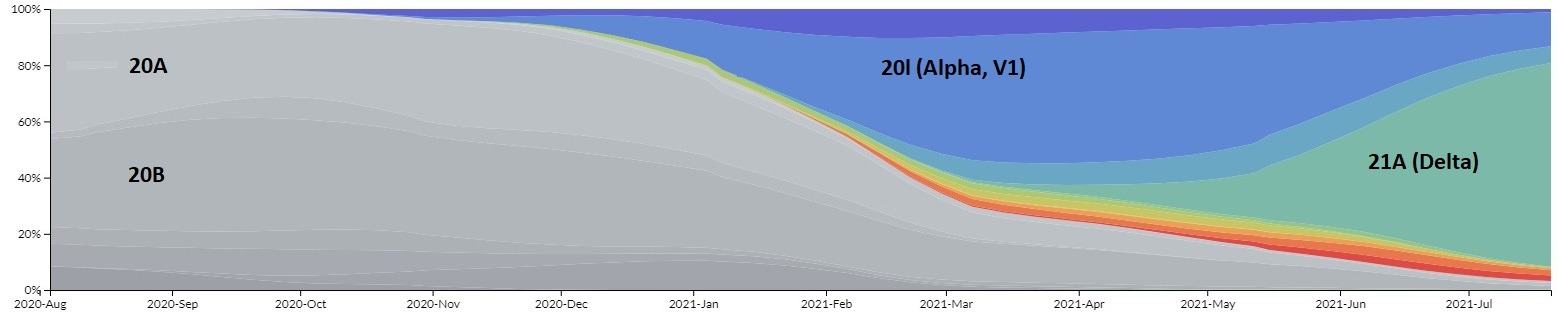

Until summer 2020, the daily confirmed cases remained below 100,000 worldwide, thanks to stringent measures against COVID-19 in China and several other Asian countries. The dominant virus (Clade 19A, 19B) and its successors (20A, 20B, 20C etc.) were more manageable than contemporary variants.

If the Trump administration and the EU had abided by the WHO’s warnings in January 2021 and launched aggressive containment measures, much of the global catastrophe might have been preempted. But such measures were initiated only in late spring 2020.

As the net effect, the mushrooming cases in the UK resulted in a variant (20l, Alpha V1) that proved far more transmissible by fall 2020. Prime minister Boris Johnson promised herd immunity and early exit from lockdowns. Yet, the reverse ensued. The spread of the UK variant was further reinforced by continued mismanagement in the US and Brazil. So, the daily new cases peaked at 840,000 in January.

The third phase followed in late spring, when the complacency of Modi’s government caused a massive spread in India, unleashing the Delta variant (21A). In May, daily new cases climaxed at almost 900,000.

In early April, Delta still accounted for less than 5% of total cases worldwide; today, that figure is almost 75% of all cases worldwide (Figure 1).

Figure 1 The great covid-19 divergence

Note. Frequencies of viral clades of SARS-CoV-2, Aug 2020-Aug 2021

Source: NextStrain; DifferenceGroup.

Vaccine inequality

By late November 2020, Canada and the US had already pre-ordered up to 8-9 doses of vaccines per person. The UK, Australia and the EU followed in the footprints with 5-6 doses per person.

In January 2021, WHO chief Dr Tedros warned that, due to the unequal COVID-19 vaccine policies, “the world is on the brink of a catastrophic moral failure and the price of this failure will be paid with lives and livelihoods in the world’s poorest countries.”

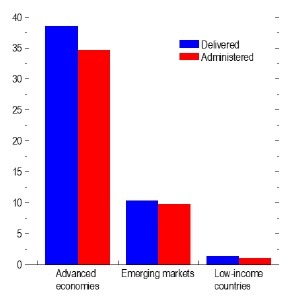

By then, 40 million vaccine doses had been given in 50 rich-income economies. By contrast, 9 out of 10 people in poor countries were set to miss out on COVID-19 vaccine in 2021, according to Oxfam.

Hence, the drastic vaccination gap between the rich and the poor around the world. The new World Economic Outlook (IMF) estimates that close to 40 percent of the population in advanced economies has been fully vaccinated, compared with less than half that number in emerging economies, mainly due to China, but only a tiny fraction in low-income countries (Figure 2).

Figure 2 The great vaccine divergence

Note. Vaccine courses (% of population)

Source: WEO, IMF, July 2021.

And things are about to get a lot more challenging. Not so long ago, the EU pledged great vaccine support to poorer economies, particularly in Africa. That was manna from heaven to the region since only 1.2 percent of the entire African population are fully vaccinated today, according to the WHO.

Yet, the realities of vaccine support have proved very different. Last week, the African Union special envoy tasked with leading efforts to procure Covid-19 vaccines for the continent blasted Europe, saying that “not one dose, not one vial, has left a European factory for Africa.”

Economic apartheid

Thanks in part to the UK and Delta variants, forecasts for advanced economies have been recently revised up, whereas prospects for emerging and developing economies have been marked down for 2021, particularly for emerging Asia.

Yet, the real challenge is that these changes may not precipitate just cyclical fluctuations, but longer-term secular shifts. In August 2020, a year ago, my COVID-19 report projected years of lost progress and plunging living standards in all economies. In particular, lost decades in poorest countries, increasing divisions, and famines and conflicts in fragile states.

Last February, nearly half a year ago, I warned that vaccine nationalism by developed economies and the consequent vaccine inequality between developed and developing economies was likely to reinforce the projected consequences. Vaccine access would become critical for sustained economic recovery, while splitting the world in two.

That’s now the new normal; one that even the IMF has acknowledged. Vaccine access has emerged as the principal fault line for the global recovery. Where the IMF and other multilateral development banks may still be too optimistic is the assumption that these initial conditions have mainly short-term consequences.

In reality, the consequent effects are likely to have longer-term impact, due to continued mismanagement and premature exits in advanced economies, vaccine inequality around the world and the resultant new variants. The recovery is not assured even in countries where infections are currently very low so long as the virus circulates elsewhere.

Apartheid is defined as a policy or system of segregation or discrimination on grounds of race, or segregation on grounds other than race. The mismanagement of the pandemic, the rise of the UK and Delta variants (and new variants to come), coupled with vaccine inequality, are resulting in economic apartheid.

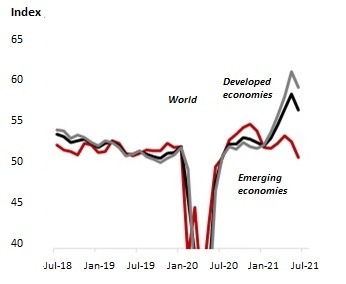

Composite PMIs (purchasing managers index) reflect the divergence between developed and emerging economies. While those of the former have surged, those in the latter have retreated over the past few months. In the short run, this is likely to mean an increasingly lopsided global recovery (Figure 3).

Figure 3 The great economic divergence

Source: DBS, DifferenceGroup

One planet, two worlds

Accordingly, near-term global recovery and longer-term economic prospects are splitting. In one bloc, advanced economies will look forward to further normalization later this year, thanks to aggressive fiscal stimulus packages, increasing debt-taking and accommodative monetary policies.

In the other bloc, developing economies – many emerging economies and most low-income economies – will face resurgent infections and rising COVID death tolls; but with limited fiscal resources, and not-so-accommodative monetary policies.

After four decades of misguided neoliberal policies, inequality is record-high within the high-income West. The stakes are reflected by the US where 7.4 million people are about to face eviction as the Biden administration refused to extend the federal eviction moratorium – while boosting military allocations. What’s far worse, however, is the increasing income polarization between the prosperous West and the poorer global South.

The ongoing economic apartheid between the high-income economies and poorer countries will foster increasing global economic uncertainty, extraordinary social turmoil, political volatility and extremist radicalization – which, in turn, the new protectionism and xenophobia in the West are likely to further inflame.

The worst is yet to come.

About the Author:

Dr. Dan Steinbock is an internationally recognized strategist of the multipolar world and the founder of Difference Group. He has served at the India, China and America Institute (USA), Shanghai Institutes for International Studies (China) and the EU Center (Singapore). For more, see https://www.differencegroup.net

Based on Dr Steinbock’s global briefing of Jul 30, 2021

- Prices push oil above $100 per barrel Mar 9, 2026

- COT Metals Charts: Speculator Bets led by Silver, Gold & Platinum Mar 7, 2026

- COT Bonds Charts: Speculator Bets led by 10-Year Bonds & Fed Funds Mar 7, 2026

- COT Energy Charts: Speculator Bets led by Brent Oil & Heating Oil Mar 7, 2026

- COT Soft Commodities Charts: Speculator Bets led by Corn & Soybean Meal Mar 7, 2026

- Investors run to safe-haven assets amid Middle East escalation Mar 6, 2026

- EUR/USD Under Pressure: Middle East Risks Outweigh All Else Mar 6, 2026

- Bitcoin shows resilience to Middle East events. Oil market stabilizes Mar 5, 2026

- GBP/USD: Market Not Expecting BoE Rate Cut in March Mar 5, 2026

- Brent headed for $100? Mar 4, 2026