By Dan Steinbock

Recently, many countries in Asia have suffered from deadly and costly epidemics. While globalization and climate change may play a causal role, germ geopolitics cannot be excluded any longer.

Entomological, anti-animal and crop-based diseases typically occur for natural reasons. All three have also be aggravated by globalization and climate change. However, evidence suggests that some of these outbreaks may also involve prior deployment in “biological programs” and “research.”

Take anthrax, for instance. Despite the post-9/11 concerns, the bacteria continue to be “researched.” In May 2015, Pentagon confirmed that its lab in Utah had “inadvertently” sent live anthrax samples to one of its military bases in South Korea. Last April, civic groups and residents took to the street to protest against biological agent experiments, which the US was reportedly conducting at Busan’s Port Pier 8. Pentagon’s budget estimates suggest the project was ongoing with funds set aside for live agent tests.

These issues remain sensitive in East Asia, in light of the US biowarfare against North Koreans and Chinese in the 1950s and contemporary geopolitics. Biological agents have dual-use functions. Like new technologies, they can save but also incapacitate and destroy human lives.

Asian Swine Fever: Epidemics Vs Geopolitics

Free Reports:

Get Our Free Metatrader 4 Indicators - Put Our Free MetaTrader 4 Custom Indicators on your charts when you join our Weekly Newsletter

Get Our Free Metatrader 4 Indicators - Put Our Free MetaTrader 4 Custom Indicators on your charts when you join our Weekly Newsletter

Get our Weekly Commitment of Traders Reports - See where the biggest traders (Hedge Funds and Commercial Hedgers) are positioned in the futures markets on a weekly basis.

Get our Weekly Commitment of Traders Reports - See where the biggest traders (Hedge Funds and Commercial Hedgers) are positioned in the futures markets on a weekly basis.

Asian swine fever (ASF) is a hemorrhagic fever of pigs with mortality rates close to 100 percent and major economic losses. Historically, the first ASF outbreak took place in Kenya in 1907 and the first outside Africa in Portugal in 1957. That’s the official story.

In reality, by the early ’50s, several viruses, including ASF, were available in Fort Terry, a US bio-warfare facility in Plum Island, New York. Between the 1960s and late ‘90s, Cuba accused Washington of ten biological warfare attacks following serious infectious disease outbreaks. None were proven conclusively, but several most likely occurred. In 1971, pigs in Havana hog farm were diagnosed with ASF virus, which caused half a million pigs to be slaughtered. As Cuba suffered food shortage, the UN labeled the outbreak the “most alarming event” of 1971.

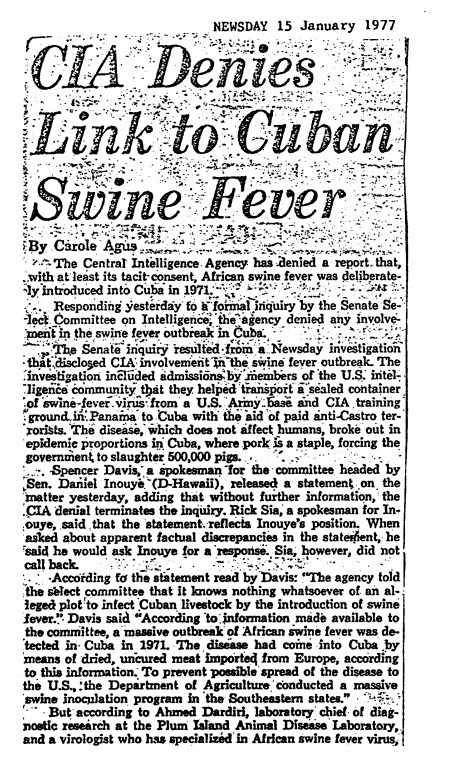

The debacle remained a mystery until 1977, when Long Island Newsday reported the virus was delivered from a US army base; the site of joint Army-CIA covert operations in the Panama Canal Zone. US Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) denied involvement. Yet, bio-warfare historian Norman Covert has affirmed CIA had access to the laboratories.

“CIA Denies Link to Cuban Swine Fever”

Following the Cold War, the ASF threat seemed to have been defused. But as a series of “color revolutions” took off in Eastern Europe – in countries targeted for NATO enlargement – the ASF in 2007 spread to Georgia in the Caucasus and thereafter widely to neighboring countries, including Armenia, Azerbaijan and several territories in Russia.

After a decade of relative quiet, the first ASF outbreak in China was reported in Shenyang in August 2018. It was thought to have come to China via Russia or Eastern Europe; that is, through the “color revolutions” countries.

The timing is intriguing. In China, the spread of ASF began with the US trade war after mid-2018. As a result, US pork sales to China were over three times pricier already last spring than a year before, despite the US retaliatory tariffs. China’s over 400 million pigs account for half of the world total. The ASF is a major threat to global food security.

US Trade War, China’s ASF Epidemic, Soaring Import Prices

China’s Breeding Saw Population, 2016-19

Source: FAO (UN), USDA (US), MARA (China)

Ethnic Bio-Bombs, Non-Endemic Outbreaks

After the Cold War, the Nunn-Lugar Cooperative Threat Reduction Program (CTRP) was created presumably to keep the former Soviet Union’s nuclear and chemical infrastructure from rogue nations and terrorists. But as Congress in 1996 began to expand the program internationally, so did efforts to capitalize on its offensive uses.

In particular, the neoconservative Project for New American Century (PNAC), the ideological force behind the subsequent Bush administration’s foreign policy, declared in its manifesto Rebuilding America’s Defenses (2000) that “advanced forms of biological warfare that can ‘target’ specific genotypes may transform biological warfare from the realm of terror to a politically useful tool.”

Previously, such efforts at biological “ethnic bombs” had occurred mainly in apartheid-era South Africa and Rhodesia; the PNAC builds on the Israeli “ethno-bomb” idea to target specific genetic traits among target populations.

By May 2007, Russia banned all exports of human bio samples, due to concern for “genetic bio-weapons” targeting Russian population. Reportedly, some of these institutions, including Harvard Public Health and USAID, have collected biological material in China as well. In October 2018, Russian Defense Ministry claimed the spread of viral diseases from Georgia, including African swine fever since 2007, could be connected to a US lab network in the area, where more than 70 Georgians had died in odd conditions.

The lab network, a branch of the Nunn-Lugar bio-initiative, belongs to the multimillion-dollar Cooperative Biological Engagement Program (CBEP) funded by Pentagon’s Cooperative Threat Reduction Agency (DTRA). The CBEP labs are located in 25 countries, including in Eastern Europe (e.g., Georgia and Ukraine), the Middle East, Africa and Southeast Asia. In several locations, there have been reported outbreaks of tropical diseases, which are not endemic to the area.

Despite high-level Russian calls for a “comprehensive evaluation” and “joint inspections,” pleas for multilateral cooperation have been ignored. In its 2020 multimillion-dollar budget, the DTRA characterizes the “bio-security” program in Asia as “the partner of choice in a region competing against Chinese influence.”

Pressing Need for Multipolar Cooperation

Even the discoverer of the devastating Lyme disease Willy Burdorfer participated in US bio-warfare, according to science bestseller Bitten (2019). That has triggered New Jersey Rep. Chris Smith’s investigation into whether Pentagon has experimented with tics and other insects as biological weapons.

International concern is rising over the role of potential covert goals in viral outbreaks. By September, the Fall armyworm, a pest that can damage a wide variety of crops, had spread to 25 Chinese provinces posing a severe threat to food security. Described first in 1797, it used to be endemic only to Americas. After the Trump 2016 win, it has globalized faster than Facebook. Only crisis measures permitted China to contain the threat “for this year.”

A new Pentagon program called “Insect Allies” funded by the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) relies on gene editing and hopes to infect insects with modified viruses, presumably to make US crops more resilient. In contrast, international scientists suggest such programs do not represent agricultural research but new bio-weapon programs, which violate the Biological Weapons Convention.

During the Cold War, the threat of the mutually assured destruction constrained nuclear and bio-warfare risks, however. The contemporary era is devoid of such constraints and thus far more dangerous. The most effective way to resolve the contested bio-warfare challenges would be to build on international multilateral biological arms control, particularly the 1925 Geneva Protocol, the 1972 Biological and Toxin Weapons Convention (BWC) and the 1993 Chemical Weapons Convention (CWC).

With rising climate risks and geopolitical tensions, no single country should have monopoly over biological agents in the 21st century. What’s desperately needed is multipolar cooperation among the major advanced economies and large emerging powers.

About the Author:

Dr. Dan Steinbock is the founder of Difference Group and has served at the India, China and America Institute (US), Shanghai Institute for International Studies (China) and the EU Center (Singapore). For more, see http://www.differencegroup.net/

A shorter version of the commentary was released by China-US Focus on October 10, 2019