By Dan Steinbock

– In the coming months, success or failure to contain the global pandemic and overcome the coronavirus contraction has potential to make or break the promise of Southeast Asia in the early 21st century.

By the end of the 2nd quarter, the total number of confirmed cases may total close to 10 million, while deaths could surpass 225,000. What was an epidemic in China at the turn of January and February grew into a pandemic in the 1st quarter, due to the belated and inadequate mobilizations in the US and Europe.

In early year, the epicenter of the virus was in China and the rest of Asia. By March-April, it had moved to Europe and the United States. As I projected three months ago, global devastation would escalate by summer as the epicenter is shifting to emerging and particularly developing economies.

The human costs of the global pandemic are mirrored by historical economic damage. As I predicted in early March, the economic impact of the coronavirus contraction would be comparable to the 1930s Great Depression. Recent World Bank data confirms the projection. The current baseline forecast envisions a whopping 5.2% contraction in global GDP in 2020.

The net effect will be the deepest global recession in eight decades, despite unprecedented policy support. As a result, per capita incomes and living standards in most emerging and developing economies will shrink this year. Meanwhile, across the world, economies are easing lockdown measures, trying to bring relief to those whose livelihoods have been drastically disrupted.

Free Reports:

Get Our Free Metatrader 4 Indicators - Put Our Free MetaTrader 4 Custom Indicators on your charts when you join our Weekly Newsletter

Get Our Free Metatrader 4 Indicators - Put Our Free MetaTrader 4 Custom Indicators on your charts when you join our Weekly Newsletter

Get our Weekly Commitment of Traders Reports - See where the biggest traders (Hedge Funds and Commercial Hedgers) are positioned in the futures markets on a weekly basis.

Get our Weekly Commitment of Traders Reports - See where the biggest traders (Hedge Funds and Commercial Hedgers) are positioned in the futures markets on a weekly basis.

In Southeast Asia, the economic fallout has barely begun.

Pandemic impact on Southeast Asia

In the coming months, emerging and developing economies will seek to cope with the coming economic tsunami. With weaker healthcare systems, the poorest economies will take the heaviest hit. The populous economies in Southeast Asia – Indonesia, Philippines, Thailand and Vietnam, or the ‘ASEAN-4’ – are not an exception.

Among the ASEAN-4, the epidemic started with only 50 confirmed cases at the end of January. Yet, at the end of June, that figure is likely to be closer to 90,000. In five months, it has increased by more than 1,650 times.

At the end of the first quarter, Philippines was worst hit (2,084 confirmed cases), followed by Thailand (1,651), Indonesia (1,528) and Vietnam (212).

By the end of the 2nd quarter – that is, June 30 – the largest case counts are likely to be in Indonesia (over 52,000), followed by Philippines (over 32,000), Thailand (3,200) and Vietnam (some 340) (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Cumulative confirmed cases in ASEAN-4

Source: WHO data, Difference Group

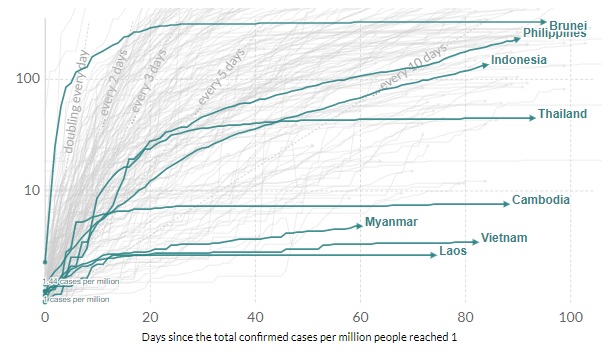

Relative to the population size (total cases/1m pop), the pandemic impact among the ASEAN-4 has been hardest in the Philippines and Indonesia, where the cases are still on the rise, followed by Thailand and, far behind, Vietnam (Figure 2).

Figure 2 Total confirmed COVID-19 cases in selected ASEAN countries*

* Log.

Source: European CDC, Difference Group, Jan 26 – Jun 13, 2020

These comparisons rely on the assumption that the figures are valid. One way to assess that validity is testing. The more countries test, the more accurately the cases will reflect the actual impact, while the reverse applies as well.

Usually upper-middle-income countries, such as Thailand, have greater testing capacity than lower-middle income economies, such as the rest of ASEAN-4. Indeed, the intensity of testing (i.e., testing per 1 million people) across ASEAN-4 suggests that currently Thailand is testing most aggressively (about 6,700), followed by Philippines (4,500), Vietnam (2,800) and Indonesia (1,800).

Internationally, Vietnam has been portrayed as a pandemic success story, due to its low number of cases. The presumed success has been attributed to rigorous testing, young population, contract tracing and isolation. Yet, realities are different.

In fact, testing intensity suggests Vietnam is at par with Bangladesh and Mexico; there is little rigorous about it. Nor is young population a reason for the success. Median age in Vietnam (31) is slightly higher than in Indonesia (30) and far higher than in Philippines (24). That leaves contract tracing and isolation, which have been called “repressive” by critics.

Those countries that test relatively less are more likely to see new virus waves and residual clusters in the future. Moreover, they will face new challenges as the economy begins to ease lockdown measures and tourism will pick up. Such countries may also see surges in mortality rates, which may not be attributed to the pandemic, but to “pre-existing pulmonary conditions” and so on.

Economic impact on Southeast Asia

As the outbreak has spread, the disruption of supply chains and temporary plant shutdowns, coupled with a sudden full stop in global demand, weigh heavily on those ASEAN economies that rely on export-led growth, remittances, tourism and travel, retail, and so on.

After the first quarter, the expectation was that ASEAN-4 will all suffer a severe growth contraction in the 2nd quarter that will cast a long shadow over the year.

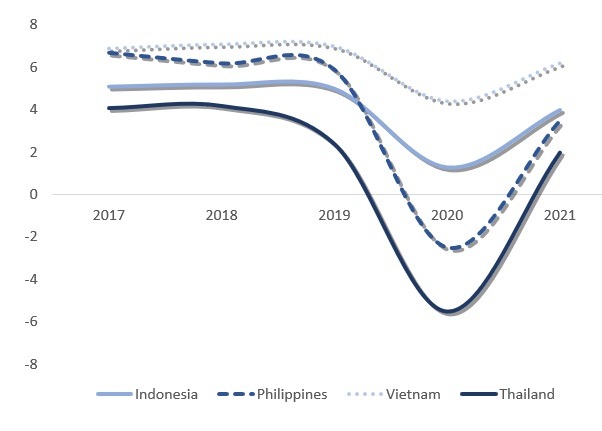

In Indonesia, the contraction would result in a plunge from 5.0% in 2019 to 0.5% in 2020; in the Philippines, from 5.9% to 0.6%; and in Thailand, from 2.4% to -6.7%, respectively. Better positioned, Vietnam’s GDP growth was expected to fall from 7.0% to 2.7%, if it could minimize the virus impact at home.

Only one quarter later, the expected plunge in 2020 has deteriorated in the Philippines, which is expected to enter negative territory (-2.5%). In Thailand, the plunge will be worse (-5.5%) but slightly improved from a quarter before. Indonesia (1.3%) and Vietnam (4.4%) would do better than expected a quarter ago (Figure 3).

Figure 3 Coronavirus contraction in ASEAN-4*

* Percent change, 2017-E2021 (GDP, constant prices)

Source: IMF data, Difference Group

Assuming a relatively strong rebound scenario, ASEAN economies could have a V-shaped rebound by 2021, when Vietnam and Indonesia (4 to 6%) could perform significantly better than Philippines and Thailand (3 to 4%)

However, since Indonesia and Vietnam have not tested adequately, economic performance in the two countries could face new downside risks if the pandemic may linger longer than expected. Conversely, Philippines and Thailand could benefit from upside risks, if they manage to keep the virus in check in the near future.

In Indonesia, external risks are cushioned but only to a degree by a narrowing current account deficit and increases in foreign-exchange reserves. As the country is easing the lockdown, recovery relies on the containment of further infection spread.

As Vietnam, as well as Singapore and Malaysia, have discovered, two years of trade wars and a few months of a global pandemic can undermine a decade of export recovery. In turn, countries that depend on both tourism and exports (Vietnam, Singapore, Malaysia) must cope with longer-term economic malaise.

In Thailand, the restart of the economy will be phased and should bring some relief in the second half of the year. Yet, recovery is likely to prove slow, due to the plunge in tourism and weakness in trade. Meanwhile, the central bank will try to keep the Thai baht below 30 per US dollar.

Philippines could have been better positioned against the crisis, but that advantage was largely lost with the 2019 budget debacle. It delayed the government’s vital infrastructure investment program, which now faces far tougher economic conditions.

Domestically, Philippines, too, must balance between targeted quarantines and gradual exit from the lockdown. In turn, consumption cannot thrive as long as supply remains limited and demand is restricted. Internationally, economic turmoil will affect Philippines through slower inflows of foreign investment, weaker export performance and significant reduction of remittances.

Margin for error slim to nil

Moreover, even the current baseline scenario could prove too optimistic. The challenges in the West could linger, while the devastation in emerging and developing economies could spill over the latter half of the year. In the US, Europe and elsewhere, new virus waves and residual clusters could ensue, while imported infections could accelerate toward 2020-21.

In turn, the development of vaccine and viral therapies could take longer than expected, while US tariff wars might pick up against China, Japan and South Korea, even Europe. And as the heavily-indebted advanced economies are now taking record-volumes of new debt to support their economies, they could face new debt crises, which would spill over to poorer countries.

In the near future, Southeast Asia will face the greatest risks (and opportunities) since World War II. The margin for error in pandemic containment and economic policies is now slim to nil.

About the Author:

Dr. Dan Steinbock is an internationally recognized strategist of the multipolar world and the founder of Difference Group. He has served at the India, China and America Institute (USA), Shanghai Institutes for International Studies (China) and the EU Center (Singapore). For more, see https://www.differencegroup.net