US-UK trade talks have begun – here’s what each side wants and what to expect

By Karen Jackson, University of Westminster and Oleksandr Shepotylo, Aston University

Trade talks between the UK and US have officially begun. Both parties are working towards a free trade agreement – a full deal, as opposed to something like the recent China-US “mini deal” that focuses on certain export targets to manage trade between the two countries. Like a lot of relationships at the moment, this one is being negotiated over video.

There are doubts over the timeline of when these talks will come to a conclusion. As well as the coronavirus pandemic, the picture is further complicated by the ongoing EU-UK talks. But at the outset of this process there are some things we know about what each side is looking to get out of a deal.

What the UK wants

The US is already the UK’s biggest destination for goods, sending 13% of its exports there in 2018. The UK wants better access for these US-bound exports, particularly food and agricultural products, though those only account for 5% of its US exports overall.

Improving market access relies on an array of factors, starting with tariffs. For example, ceramics face a particularly high tariff of 28%, as do some categories of textiles, at 32%.

Agreement must also be reached on rules of origin, where there is a joint understanding as to how the origin of each product will be decided. This is very important since 70% of trade involves global value chains, so most goods have value added by producers from more than one country. This means that deciding on a single origin for each product is tricky and may have an impact on the costs of trading, since various duties depend on the origin of the product. Further issues involve technical barriers to trade, standards, and agreements on testing procedures.

Free Reports:

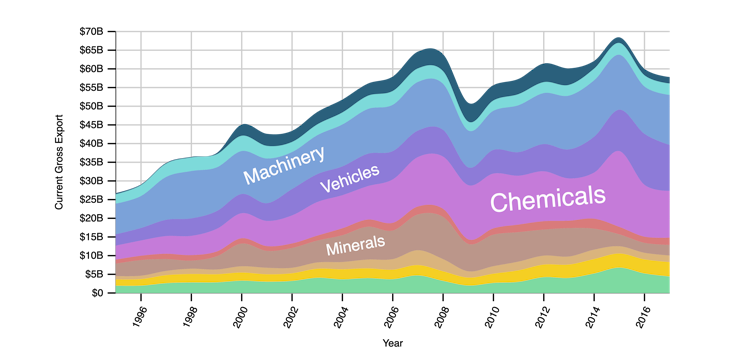

Atlas of Economic Complexity

As well as goods, trade in services is also on the agenda. The UK is keen to see improved market access for UK services in accountancy, architecture and finance, as well as freedom of movement and mutual recognition of professional qualifications.

What the US wants

The US already has lower tariffs than the UK for most categories of goods, so it would expect more concessions from the UK side in this regard. For instance, US tariffs on imported cars are 2.5%, while UK tariffs are 10%.

The UK currently meets EU regulations for environmental, fuel efficiency and safety standards for cars. A comparison of EU and US regulations shows numerous differences: the US directly sets minimum fuel efficiency, while the EU does not; the EU and US have different emission standards. Even seatbelt regulations differ. This has important implications for how cars are built, making it more difficult and expensive to export cars to both markets.

The US team will also push for US products to be traded more freely in the UK market – hence, chlorinated chickens and other agricultural and food products produced according to US standards.

When it comes to services, the US will want to better access for its healthcare and pharmaceutical companies. So even though the UK government says that the NHS is not on the table, we can expect US negotiators to try and gain access to it.

EU looms large

These UK-US negotiations cannot be separated out from those between the EU and UK, since US demands are bound to clash with some EU rules and regulations. This will lead to a painful trade-off for the UK, which will have to choose between closer economic ties to either the EU or US.

The fact that the US is a much smaller trade partner than the EU means potential gains from the UK-US deal are quite small. When you add the issue of regulations to this – the UK and EU are already much more closely aligned, whereas the US has a much more liberal policy environment – the UK has a lot to lose from worsened access to EU markets.

Atlas of Economic Complexity

We show in our research that even if the UK manages to secure preferential trade arrangements with the US and the Commonwealth countries combined, it will not offset the negative impact of Brexit. Because the EU is the UK’s biggest trade partner, the UK will benefit the most from securing a full free trade deal with the EU.

Negotiating tactics

The UK is using an interesting negotiating tactic of launching simultaneous trade talks with the EU and US. The idea is that if it achieves good progress in its trade talks with the US, it can use this as leverage to influence negotiations with the EU.

This approach has been criticised by some trade experts because it spreads the UK negotiating capacities too thin and creates difficulties in coordinating these talks. The fact that the negotiations must now be carried out remotely makes it even more difficult due to the logistical constraints of talking over video.

The US-Japan Trade Agreement came into effect this year after six months of negotiations and using a fast-track approvals process in the US. However, this was really only another mini-deal concentrating on tariffs and digital trade. This suggests that a comprehensive UK-US deal will take much longer and would need a vote in Congress.

In between dealing with the COVID-19 outbreak and the associated economic fallout, as well as the US elections, it may take a while before we see any results from these virtual negotiations. And we must remember that the UK government’s own modelling suggests that a deal will bring limited economic gains for the UK.

About the Authors:

Karen Jackson, Senior Lecturer in Economics, University of Westminster and Oleksandr Shepotylo, Lecturer in Economics, Aston University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.